While I love the film version of The World According to Garp, I’ve never read a John Irving novel. I should rectify that at some point, but I mention it here to illustrate that I’m missing what Stephen King cites as a significant influence on Shaun Hamill’s A Cosmology of Monsters. That being the case, I still loved Hamill’s book. A Cosmology of Monsters strikes a perfect balance between a literary and genre horror novel. Fans of works at either end of the spooky spectrum should appreciate this tale.

While I love the film version of The World According to Garp, I’ve never read a John Irving novel. I should rectify that at some point, but I mention it here to illustrate that I’m missing what Stephen King cites as a significant influence on Shaun Hamill’s A Cosmology of Monsters. That being the case, I still loved Hamill’s book. A Cosmology of Monsters strikes a perfect balance between a literary and genre horror novel. Fans of works at either end of the spooky spectrum should appreciate this tale.

Before I talk about the story, I need to laud this book’s gorgeous exterior (pictured to the left). The cover stopped me dead in the store the first time I saw it. I loved the evocative illustration combined with the bright orange and blue hues. A special shoutout is owed to Na Kim and Kelly Blair, who are listed as being responsible for the jacket illustration and design, respectively. They, and Pantheon Books, did a terrific job on the eye candy. That said, I will now jump into the actual narrative.

Spoilers Below (although I try to keep things vague)

The idea of a horror novel based around a haunted house attraction is brilliant, and that alone might’ve been enough for me to enjoy this work. Yet, by the end of the story, that aspect feels like a minuscule part of the book. The opening pages follow the protagonist’s mother and father, a huge Lovecraft fan, as they start their relationship and marriage. Unfortunately, things take a tragic turn for the father, who dies of cancer. From there, the story focuses on Noah, the youngest son of the couple, as he grows up. His childhood is complicated by the appearance of a monster, who he befriends, and the disappearance of his sister. Eventually, after many twists and turns, Noah discovers a hidden world in which monsters are made, and he must make some horrible choices to save the people he loves. There are a lot of details I’m leaving out, but that was just a quick summary. You’ll need to pick up a copy of the book for the full yarn.

I enjoyed this entire novel, and I read it in only three sittings. There were two standout moments for me. The first was a sexual scene between the monster and Noah. This scene surprised and confused me, and I’m impressed anytime a writer does that to me. Eventually, the scene makes sense as it’s foreshadowing a later revelation, but in the moment, I was befuddled and couldn’t make heads or tails of it, and I just loved that feeling. The second standout moment of the book was the ending. It’s a gut-wrenching ordeal where the protagonist makes a Faustian bargain. I’ll let you discover the choice Noah makes for yourself, but I was impressed by how dark the story got in the end. Conclusions are where many tales fall flat, and I was happy to discover that A Cosmology of Monsters did not. I was left wanting more stories set in the universe of this book. Hopefully, one day Shaun Hamill will continue Noah’s dark journey or give us a new protagonist’s insight on the dark city at the heart of this narrative. That said, based on reading this novel, I’ll be happy to check out whatever Hamill does next. If I still haven’t sold you on A Cosmology of Monsters, you should give a listen to Shaun Hamill’s interview with the Lovecraft ezine for further enticement.

When I first read H.P. Lovecraft’s The Colour Out of Space, I was immediately excited at the thought of writing a sequel. The ending makes continuing the story an enticing proposition. When I investigated the subject, I found Michael Shea had already written a second installment, The Color Out of Time. This didn’t stop me from writing my own follow-up,

When I first read H.P. Lovecraft’s The Colour Out of Space, I was immediately excited at the thought of writing a sequel. The ending makes continuing the story an enticing proposition. When I investigated the subject, I found Michael Shea had already written a second installment, The Color Out of Time. This didn’t stop me from writing my own follow-up,

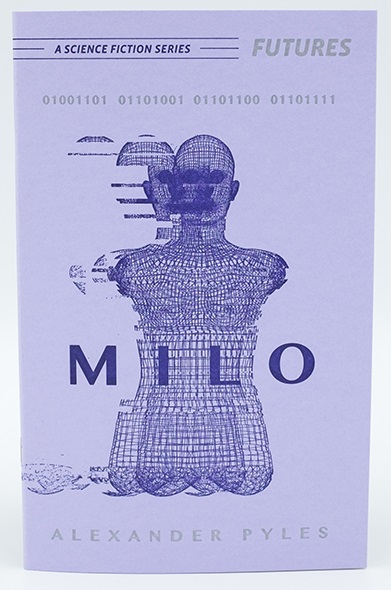

01001101 01101001 01101100 01101111 00100000 01101001 01110011 00100000 01100111 01101111 01101111 01100100 (

01001101 01101001 01101100 01101111 00100000 01101001 01110011 00100000 01100111 01101111 01101111 01100100 (